Some recent posts have described the three pipe organs located within the Kirk of St Nicholas over recent decades. To complete the picture of musical instruments in the building, this post deals with a harmonium (also called a reed organ) located in St Mary’s Chapel.

Harmoniums were developed from the late 18th century, reaching their peak around 1900. They work by causing thin pieces of metal, held in a frame, to vibrate by passing air over them. The piece of metal is called a reed, hence the name of this type of organ. The pitch of the sound is defined by the length of the reed, whilst different tones and volumes can be produced by using different shapes of reed, angle of air impact and by surrounding the reed in a tone chamber. Traditionally the air flow is produced by the player using two foot treadles, like an old fashioned sewing machine, to operate bellows. Some larger instruments also have hand operated bellows, worked by an ‘assistant’. A second type sucks the air over the reed rather than blowing it. In general this produces a softer, quieter sound, making it more suitable for home use. As with a pipe organ, the harmonium is played from a keyboard, each key allowing air to pass over one reed. A range of stops is used to produce the different sound qualities desired, as with the pipe organ. With some instruments the volume can be altered using a knee-operated air valve.

Harmoniums are relatively easy to transport and are more robust than a piano. They are also less complex and so many churches could afford them whereas a pipe organ was beyond their financial resources. Many are still in use in this context. Smaller harmoniums are also widely used in Indian and folk music.

The instrument in St Mary’s Chapel has a single manual and range of stops, and is ‘blown’ using two foot treadles. It is shown in the first photograph. Until fairly recently it still worked, but of late has ceased to do so, probably because the leather in the bellows needs replacing – a common problem with time! Looking at the photograph, it is possible to see that there is something at the front of the left hand treadle. This is a small notice to say the mechanism is patented ‘mouse proof’! The knee crescendo levers are just visible above the treadles under the keyboard.

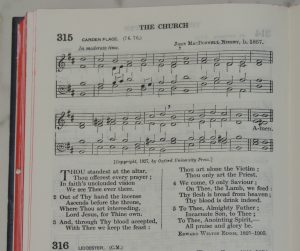

On the harmonium is a plaque, shown in the second photograph. It commemorates John MacDonnell Nisbet, who died in 1935. He became organist of the East Kirk in 1890 at the age of 33 and served for 45 years until his death – a remarkable achievement and a sign of great dedication. He also taught music to trainee teachers and lived for some time in Union Grove, later moving to Carden Place. Not only did he serve the congregation and choir faithfully, he was involved in wider church music, serving as a member of the committee responsible for producing the Revised Church Hymnary, published in 1927. Included in that book is a hymn tune called ‘Carden Place’ written by John Nisbet, shown in the third photograph.